Key Takeaways

- If the economy slides into a recession, the impact will likely be milder and shorter than the 2007-2009 recession.

- Banks are on stronger footing than they were then, meaning there's less risk of failures or contagion. And low housing inventory means a crash in prices is unlikely.

- The job market is tight, and consumers and companies generally have stronger balance sheets now than they did then.

- Taken together, these factors mean an eventual recession is unlikely to look like a repeat of the 2008 crisis.

Talk of recession has many worried about a repeat of the 2008-2009 Great Recession, when the economy lost more than 8 million jobs and the S&P 500® plunged more than 50%. But that was the economic equivalent of a 100-year flood—an unusually deep downturn precipitated by a financial crisis and the collapse of the housing market.

The good news: A much stronger economy today makes a repeat unlikely, according to Fidelity's Asset Allocation Research Team (AART). "The next recession is likely to be relatively short and mild," says AART analyst Cait Dourney. "That's because banks, consumers, housing, and the labor market are all much better positioned than they were 15 years ago."

Let's take a deeper look at these 4 areas:

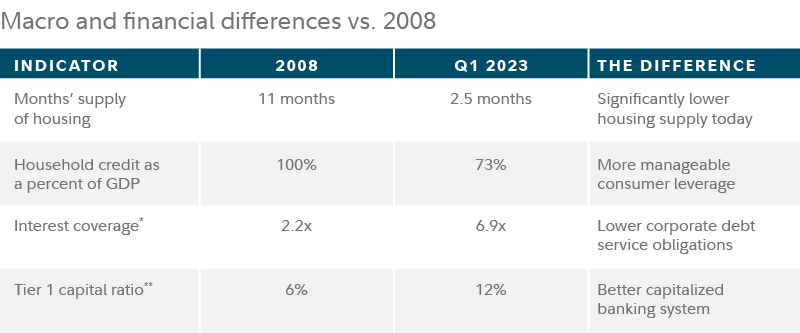

1. Banks are generally in much stronger financial shape

The banking sector has attracted heightened scrutiny this year amid turbulence at some regional banks. But still, the sector as a whole is considerably more fortified than it was in the lead up to the 2008 financial crisis.

What happened back then?

The subprime mortgages that helped inflate the US housing bubble in the early to mid-2000s had been bundled into complex financial products like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). Banks had invested heavily in these assets and when the housing market crashed, losses cascaded across the financial sector, leaving many institutions unable to meet their financial obligations. This resulted in contagion spreading across the financial sector—from Wall Street to main street—as credit markets froze and businesses and consumers struggled to borrow capital. Bank failures surged from 3 in 2007 to 148 in 20091 —a figure that might have been higher had the US government not intervened with emergency rescue measures.

Why it's different now

One upside to the financial crisis was that it led to more regulatory oversight of financial institutions. Far-reaching legislation was passed, such as the Dodd-Frank Act, which aimed to reduce risk and increase transparency.

US banks are now subject to heftier capital requirements, particularly the largest megabanks. "The big banks are now very well capitalized," says Dourney, noting that according to some measures, big banks now have twice as much in capital, relative to assets, as they did in 2008.

These megabanks are also required to undergo annual stress tests to make sure they could continue to operate in the face of a hypothetical "severe global recession."

Why it matters

The regulatory guardrails and capital requirements put in place in the wake of the 2008 recession will likely go a long way toward preventing a repeat of the financial crisis. With this in mind: If a recession were to materialize, it's quite possible there will likely be fewer bank failures, quicker containment and supportive action from policymakers, and reduced risk of calamitous shockwaves spreading across the financial system.

*Measure of a company's ability to pay interest on its debt. **Ratio of a bank's equity capital vs risk-weighted assets. Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bank for International Settlements, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Fidelity Investments (AART), as of 3/31/23.

2. The US labor market has tightened significantly since 2008

Despite recession fears and some recent high-profile layoff announcements, the labor market in 2023 has remained tight, and unemployment has stayed close to historic lows.

What happened back then?

As the 2008 financial crisis struck and the economy swiftly contracted, job losses sharply accelerated. The employment downturn—the most severe since the end of World War II—impacted a broad swath of industries. While job losses were most prevalent in cyclical areas like manufacturing and construction, even retail, leisure, and hospitality experienced declines.

At the start of the Great Recession in December 2007, the unemployment rate stood at 5%. By October 2009 it had reached 10%. And the subsequent recovery was slow: It would be another 5 years before the unemployment rate returned to its pre-recession level.

Why it's different now

The employment landscape in 2023 is significantly different. Despite the headwinds of inflation and interest-rate hikes, unemployment has remained historically low, staying below 4% since February 2022.

One key factor, says Dourney, is that US society has aged since 2008. As older workers have continued to retire, a tight jobs market has persisted. The labor force participation rate stood at 62.6% in June 2023, down from 66% in December 2007.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

3. There's less risk of a housing crash

To prevent a repeat of the housing crisis that occurred during the Great Recession, regulatory changes, including stricter lending standards, have been implemented.

What happened back then?

As previously noted, the US housing sector was among the key catalysts of the 2008 recession. The housing market experienced a bubble in the mid-2000s, with surging prices fueled by easy access to subprime mortgages (loans to less creditworthy borrowers). In addition, many homeowners had adjustable-rate mortgages, meaning the interest rate changed over time. In the latter part of the decade, as those rates began to rise and housing prices started to decline, many homeowners ended up owing more on their mortgages than their properties were worth, leading to a spike in foreclosures and a collapse in prices in some parts of the country.

Why it's different now

Compared with 2007-09, there has been a significant decline in the available inventory of homes for sale. One reason for this has been relatively low levels of new construction in the decade following the Great Recession. Another is that the low interest rates of 2020 and 2021 prompted a surge of buying and refinancing. Thirty-year mortgage rates fell to as low 2.65% in January 2021, but have since more than doubled. Homeowners appear to be more reluctant to sell their properties due to the prospect of a new mortgage with much higher rates.

Source: US Census Bureau, Department of Housing and Urban Development

The monthly ratio of new homes for sale to new houses sold stood at 5.8 in May 2023 compared with 11 in December 2007.2

"There's a lot lower supply and we've had less construction and less borrowing," Dourney says. Residential investment—a component of GDP that includes construction of new single-family and multifamily structures—peaked in the first quarter of 2021 and has already declined more than 20%, Dourney says.

"That's the normal peak-to-trough recessionary decline, so in some ways we've already had a housing recession. Now we're at a point where housing activity is actually bottoming out, sales are starting to pick up, and prices are starting to firm."

Why it matters

The severe nationwide decline in housing prices that we saw during the Great Recession is unlikely to repeat itself. Adjustable-rate mortgages are far less common today than they were in 2008. And with more homeowners locking in 30-year mortgages when rates were lower in the past few years, there is a greater likelihood that they can hang on to their properties in the event of an economic downturn. These factors mean there is far less risk of foreclosures and less inventory for potential buyers, which helps keep prices from falling.

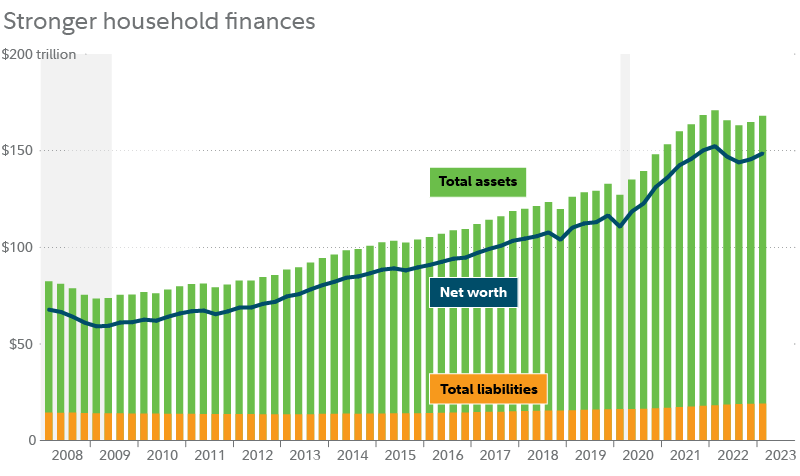

4. Corporate and household balance sheets are stronger

Despite the roaring inflation of the last few years, a period of low unemployment, pandemic-era stimulus payments, and a resilient stock market have left many households with ample cushioning should a downturn occur.

What happened back then?

In the years leading up to 2008, corporations and households had become highly indebted, making them vulnerable to the economic upheaval that was to come.

Low interest rates in the early 2000s made short-term financing more appealing for banks and corporations. But liquidity challenges arose when credit markets froze and access to financing became harder and scarcer.

At the same time, many consumers had accumulated ballooning debt from mortgages and credit cards, creating perilous conditions when unemployment started to rise.

Why it's different now

Thanks to a higher savings rate during the pandemic, plus recent gains in wages and generally lower levels of debt, households are financially stronger than they were in 2008. "If you look at consumers' net worth, it's almost at all-time highs in the 70 years or so of data," says Dourney. "Even after the disruption in the capital markets over the last year, it's only 2% off of all-time highs, so consumer balance sheets are starting from a strong point and consumer debt is also significantly lower." This should help consumers stay on sturdier footing even if unemployment were to rise.

Source: Federal Reserve

Another aspect of the current business cycle that contrasts with the prior era is corporate debt. A lot of companies refinanced their debt during the pandemic and have more longer-term fixed rates, meaning they've felt less impact from the Fed's rate hikes.

Finally, a strong consumer has helped further bolster the corporate sector. Buoyant consumer spending has supported margin expansion for many businesses. Furthermore, a combination of cost cutting and decelerating inflation has helped companies defend their margins, Dourney says.

Why it matters

"Companies, like consumers, just have a buffer that prevents them from having to really start to lay people off or cut costs or retrench," says Dourney. "What helps is that the level of profitability is so much better than it was pre-2008."

Recession outlook

Of course, no one can predict the future and all manner of unforeseen factors could change the economic picture—for better or for worse. Yet with all things considered, there is a high probability that the next recession will be less severe than 2007-09.